How Anime and Super Sentai Shows Sustained Filipino Imagination of Heroism and Humanity

Posted on 13 June 2020

By Noel Gaton, Christian Bernard Melendez, Ian Christopher Alfonso, and Juan Paolo Calamlam; edited by Maria Gloria Gabrielle G. Reyno

This Independence Day, four Batang 90s of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines—now a senior museum curator, a State heraldry officer, a senior history researcher, and a presidential museum curator—ponder that anime shows on TV actually helped their generation be educated about compassion and goodwill, and sustain their imagination on the triumph of humankind over darkness (i.e., adversities, struggles) with kabutihan (humanity); and they proudly claim they had a time well spent with their humble second-hand black-and-white de-pihit and de-pukpok na kubang surplus analog TV.

Our folklore and history teem with heroism and compassion. Next year, the country begins the 2021 Quincentennial Commemorations in the Philippines (2021 QCP) with the theme Victory and Humanity. Victory represents the triumph of our heroes since the Battle of Mactan—an event that will turn 500 years on 27 April 2021; Humanity, on the other hand, embodies the kindness our ancestors in Homonhon, an island now under the jurisdiction of Guiuan, Eastern Samar, exhibited to the sick and hungry crew of the Magellan-Elcano expedition, the first to voyage around the planet, on 17 March 1521. These twin mega events will be the Philippine government’s stake in the quincentennial (500th anniversary) of the achievement of humankind and Science in circumnavigating the world for the first time.

READ: Let the Quincentennial Begin

But even before we, the Batang 90s—Pinoy kids who have memories of the 1990s and now active members of society—were able to acquaint ourselves with most of our heroes through HEKASI (Heograpiya, Kasaysayan, at Sibika), we were previously heavily exposed to a variety of heroic narratives through anime and super sentai shows on TV. TV networks saw us as a great market, thus, the period between the post-EDSA 1 (late 1980s) and early 2000s was considered by some as the golden age of anime and super sentai, which was also a global phenomenon. Batang 90s will argue that they were able to watch quality anime and super sentai which resonates with them to this day.

Our reckoning period for a Batang 90s is between 1980 (a kid who experienced at least the first two years of the 1990s) and 1994 (at least six years of age by 2000 to have childhood memories of the world of the 90s or the last two years of the 20th century). Those who were born in 1986 were the perfect Batang 90s, for they enjoyed the rest of the decade being a Pinoy kid and have the pristine generational memory at the age of four by 1990.

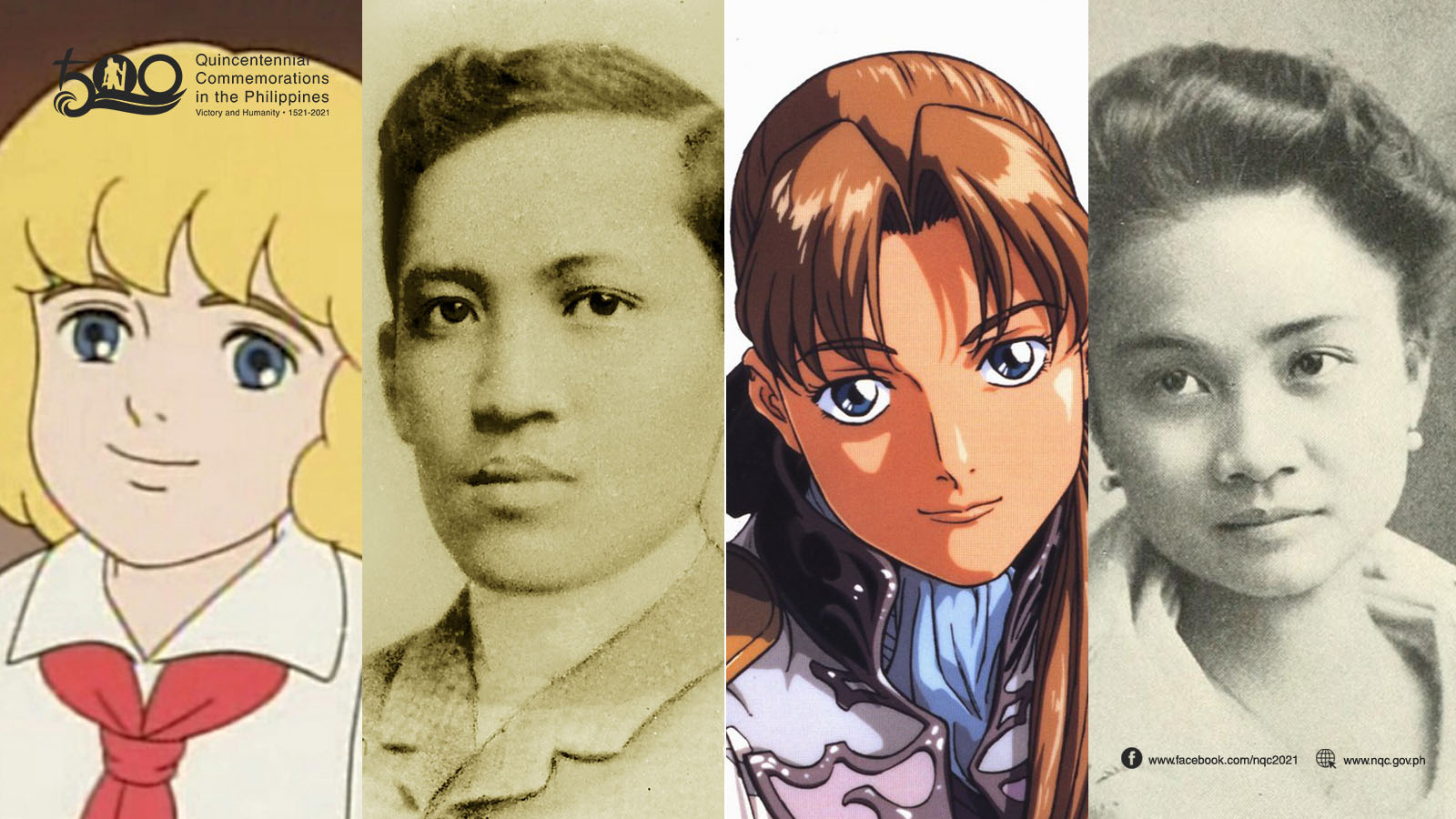

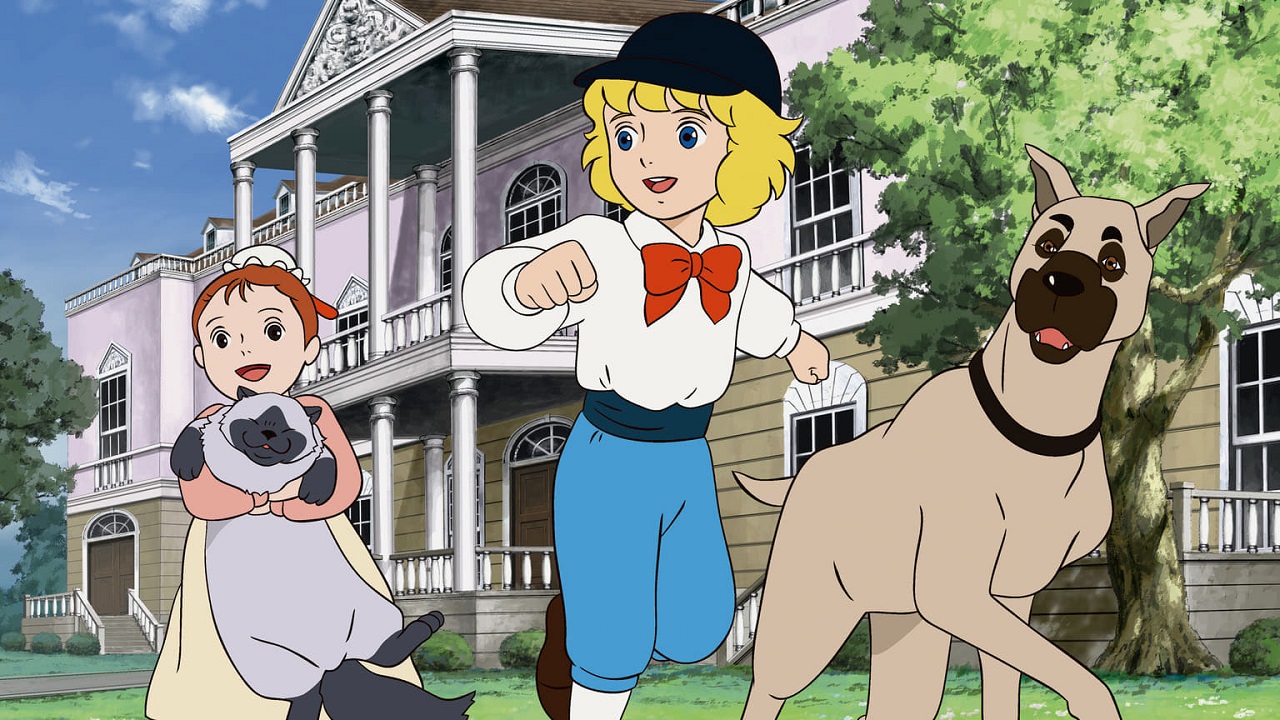

Mahal na Konde

By Noel Gaton. My friends will be surprised by this revelation: I like Cedie, Ang Munting Principe (ABS-CBN, 1996) the most, considering that most friends know me to be a ‘hustler’ in detailing the narrative of each and every anime show. Batang 90s remember Cedie as one of the few cartoons whose theme song was left Japanese (along with Heidi). (I could not remember if Princess Sarah had a theme song at all.) Contemporaneous anime shows during weekday mornings had Filipino theme songs: Remi, Si Mary at ang Lihim na Hardin, Charlotte, and Cinderella. To a Batang 90s, Cedric Errol or Cedie was iconic because of his kulay mais (‘corn color hair,’ meaning blond) and his joyful character.

Emphasis supplied on joyful character because up to now Cedie is my benchmark of patience and cheerfulness in life. He is an outsider (for he is a New Yorker prejudiced against upon living in Dorincort, England) who did his best to be acknowledged for who he is and his humble origin. He is a resolute one who, it seems, does not know how to surrender until he wins someone’s heart and achieves something. Eventually, he gains the affection of his strict and aloof grandfather (we call him Mahal na Konde), the latter becoming a changed man.

In general, I think Cedie was our epitome of humility and compassion back then. He descends from dugong bughaw or aristokrata yet he is magnanimous and people-smart. (Later on, in HEKASI, the words dugong bughaw and aristokrata would have a sense as our teacher equated these with the maharlika or noble class of ancient Philippine society. When I became a History major, our history professors corrected the misuse of the word maharlika as noble class. The right term is actually maginoo. Read William Henry Scott’s “Filipino Class Structure in the Sixteenth Century” here.) To all the Batang 90s who watched Cedie, didn’t we imagine ourselves to be as cool as Cedie (well, girls would definitely say they imagined themselves to be as good as Sarah)? Now is the time to be like Cedie (and Sarah). To be fair with the fans of Sarah, I wanted to insert here the favorite quote of my fellow, Ian Alfonso, which he remembers from Sarah: Nasaktan ko na siya sa isip ko (I already hurt her in my mind). This is from an episode when Lottie asks Sarah why not the latter fight back Lavinia. Ian said it is one of the few lines he could remember and has been his mantra in life.

Our parents would unanimously agree that Cedie was far better than the likes of Gundam Wing. And they did actually think that anime shows in the morning were family-oriented, most likely because they could monitor us watching them; unlike in the afternoon, when action-filled anime shows were (e.g., B’t X, Samurai X, Zenki) and our guardians were busy preparing for the dinner and other afternoon chores, preventing them to appreciate the story. Now that we are entitled to our own opinion, I could say most of the anime shows we used to watch were good.

From Nanay’s Ipit

By Christian Bernard Melendez. Afternoons, after class, found this Batang 90s flocking to the house of his classmate to catch Gundam Wing (along with Mojacko). It was the first Gundam series shown in the Philippines (via GMA 7) months before the end of the school year 1998-1999—probably the most loved Gundam franchise of the Filipinos. Our parents and oldies were often in shock seeing us enjoy what to them was a violent show. But little did they know, this futuristic anime made us actually contemplate the struggle of maintaining peace and the triumph of goodwill over evil. Gundam Wing is actually set in the chaotic future, when humanity extends its colonization into outer space. But advancement always comes with debacles. In this, I appreciate Gundam Wing protagonist Relena Peacecraft. She initiates peace and goodwill among human beings, which is a reflection of her origin: Sanc Kingdom, a realm known for its heritage of magnanimity. The story ends when Relena convinces the world and the Gundam pilots to consider diplomacy as an alternative to war.

I am actually glad that most of the Batang 90s I know are vocal of their views on matters affecting our society (e.g., inequality, bullying, discrimination, corruption, injustice)—thanks to social media. These are the same people previously viewed as numb and less nationalistic for just watching cartoons and playing outside their homes the whole day. Anyway, I’m sure these people have appreciated the message over entertainment in each and every anime show they watched.

Like the Gundam fans back then, I fed my craving for Gundam Wing toys by building our own out of ipit sa sinampay (clothespin) from the laundry basket of our mothers. Adulting did not stop us from feeding our Gundam nostalgia by collecting Gundam toys up until today.

(P.S. We did collect posters hawked outside our schools. Some five years later, internet cafes mushroomed all over the country, giving us the opportunity to print out the early online entries on Gundam, adopting Heero Yuy, also a protagonist, as our Friendster profile wallpapers, and listening to “Just Communication,” Gundam Wing’s theme song, on the archaic YouTube. Around that time, the so-called CD-burning became a fad and “Just Communication” joined our Batang 90s selection.)

Theme Song of Our Lives

By Ian Alfonso. Thanks to Google, we can now understand the meaning of the Japanese theme song of anime and super sentai shows we grew up with. This, aside from the life lessons in the adventures and missions of the characters to save humankind from evil and the world from destruction. But there were anime theme songs sung in Filipino and once upon a time became the soundtrack of our lives. One of these songs was that of Magic Knight Rayearth (1994, aired in the Philippines on ABS-CBN 2 in 1996), to wit:

Kami’y narito, asahan niyong magtatanggol

Makikipaglaban para sa kapayapaan.

Ang lahat ng nilalang dito ay may karapatan

(Sa magandang bukas)

Kung mayroong gumugulo ay huwag mag-alala

Kami ang dakilang tagapagtanggol niyo

Sa lahat ng oras

Handa kaming tumulong.

Ang aming mga kapangyarihan,

Alay sa karapatan.

Kami’y narito, asahan niyong magtatanggol,

Makikipaglaban para sa kapayapaan at kaayusan,

Kami’y asahan niyo

Hanggang sa dulo ng mundo.

I am sure this very song is still alive in the memory of tens of millions of Batang 90s. The lyrics and the narratives of anime show broadened the Batang 90s’ concept of heroism and compassion.

I learned from Danny Mandia, the celebrated Father of Modern Dubbing Industry in the Philippines, that when he pioneered the dubbing of Japanese anime to Filipino in 1990, he made sure all the imported materials to be shown us, Batang 90s, would impart values. His effort to translate to Filipino the said anime shows (he called “Tagalized cartoons”) ultimately proved effective. Some of these were Ang Pasko ni Santa (1994), Peter Pan & Wendy (1992), A Dog of Flanders (1994), B’t X (1997), Charlotte (1998), Cinderella (1999), and Remi, Nobody’s Girl (1999). Towards the latter part of the 1990s, the Batang 90s witnessed the rise of Filipino-dubbed anime, thus, sustaining how the Filipino kids imagined the heroic virtues of humanity and triumph. One of these anime shows was Magic Knight Rayearth (shown on Philippine TV in 1999).

Mandia, who was the dubbing director of the Magic Knight Rayearth, explained that they opted to rewrite the lyrics while using the same melody of the Japanese theme song. The translation is often associated with him but he clarified that it was a collaborative work. (The only theme song Mandia claims his is that of Remi, Nobody’s Girl, also an iconic Batang 90s’ song.) It also became a practice among other dubbers to rewrite the theme songs.

Defender Mode

By Juan Paolo Calamlam. Along with the post-EDSA 1 steady rise of the anime in the Philippines was a popular Japanese genre then called tokusatsu (“special filming”) superheroes or super sentai (“task force or squadron”). It is characterized as live-action shows involving masked and costumed heroes who battled against monsters and other villains. Special effects were also used such as camera tricks and CGI (that for us were the best and we were accustomed to it). Example of these are Bioman, Shaider, Ultraman, Kamen Rider Black, Five Man, and Jet Man (all these actually competed against the Mexicanovelas of our mothers, titas, and oldies). Americans also boarded the hype train with Power Rangers, Mask Raider Man (remember the insectivores?), and VR Troopers. (Still familiar with the line in the theme song “Countdown control: 4, 3, 2, 1. VR, VR, VR… VR troopers! Virtual reality, troopers!”, on ABC 5, now TV5?)

A recurring theme in the super sentai genre is the defense of Earth against extraterrestrial invaders (e.g., kaiju or giant monsters, alien armies). Eventually, I was introduced to our very own 16th-century heroes beginning with Lapulapu, the unnamed general from Macabebe (back then, the textbooks confused him as Rajah Soliman of Manila), and the Tondo conspirators who had the same goal: defend their homeland from foreign invaders (i.e., Spaniards). We were also taught how our ancestors in Muslim Mindanao kept their homeland uninvaded. Many more heroes were soon introduced—almost countless, making me realize the Philippines alone lacks no heroes.

Through super sentai shows, we were given the impression that a hero could be anybody. More often than not, heroes from this genre started as ordinary people or foot soldiers who, despite their powerlessness, had genuine concern for humanity. It was only by a stroke of luck or destiny that they encounter an extraordinary ability to turn the tides of an otherwise losing battle. Our real heroes in history were no different. Some prominent Filipinos such as Andres Bonifacio and Apolinario Mabini started off as common folks, but were seen with extraordinary virtues since childhood. As they grew amidst conflicting times, they met opportunities to change the fate of Filipinos. And, just like how the protagonist in Ultra Man grabbed the Ultra Capsule to make him the titular hero, our real-life heroes steadfastly grabbed the opportunity which, later in history, turned them into giants. Unfortunately, prejudices to these kiddie shows prevented our teachers from drawing parallelisms in order to spur appreciation in our own heroes.

Summing Up

There were indeed times during our childhood days that we and our respective classmates imagined ourselves to be anime characters. And yes, our parents and the elderlies saw our craziness for anime a threat not only to our health (well, radiation exposure, they said) and wellbeing (violence in what we see) but also to nationalism (the perennial issue of colonial mentality and the evil that was globalization). The rise of anime vied for attention among us Batang 90s because during that decade, the nation was celebrating the Decade the Centennials of Filipino Nationalism, Nationhood and the Philippine Revolutionary Movement from 1988 to 1998. But to us kids of that decade, TV programs exposed us as well to educational shows, such as Batibot (began on RPN 9, now CNN Philippines, in the 1980s and then on ABS-CBN 2 and GMA 7 in the 1990s), ABC 5’s 5 and Up (1992), ABS-CBN 2’s Bananas and Pajamas (1998), and the School on Air series of the late Gina Lopez Atbp: Awit, Titik at Bilang Pambata (1994), Sine’skwela (Science and Technology, 1994), Hiraya Manawari (Values Education, 1995), Bayani (Philippine History, 1995), Math-Tinik (Mathematics, 1997), Epol-Apple (English, 1999), and Pahina (Philippine Literature in Filipino, 2000). These were even beefed up by the general knowledge being shared daily by the late Ernie Baron after his weather report on TV Patrol and on his Knowledge Power program both on DZMM and TV on Saturdays.

(The National Quincentennial Committee is happy to have collaborated with National Artist Ryan Cayabyab, composer of the iconic theme songs of Sine’skwela and Hiraya Manawari, and Mr. Jungee Marcelo, composer of the theme song of Math-Tinik, in creating the 500 Years Philippine Playlist through PhilPop.)

Inter-generational gap is a vicious cycle. Every generation is biased and always has the tendency to believe that the generations younger to them are ever-awry. In our history conferences, there are always these older people who air their dismay over the younger generations (“ang mga kabataan ngayon wala nang pagmamahal sa bayan at pagpapahalaga sa kasaysayan”). We do believe our youth are not numb but always receptive to what they think are worthy of their time and attention. It’s an ever-wake up call to those who are given the chance to condition the environment of the younger people. If we demand nationalism from them, then we should increase the number of TV and radio discussions, social media programs, and other communication platforms about history and culture. Graphics and effects are now way sophisticated and the sources of information are countless. One can no longer please a Pinoy kid into watching at 40-minute to an hour historical episode because of the phenomenon of diminishing attention span in watching. Also, history can now be learned through memes, vlogs, and Facebook groups. I think the clamor of the Batang 90s for the younger generation to be like us—educated by eTVs, inspired by anime shows —is nothing but nostalgia.

Special thanks to Ms. Ann Sandig for the covers of some iconic anime and super sentai theme songs.

About the Authors and the Editor

Noel Gaton is the Museum Curator II of the Museo ni Ramon Magsaysay, one of the 27 history museums of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) located at Castillejos, Zambales celebrating the memory of President Ramon Magsaysay, the idol of the masses. He earned his BA History degree from the Polytechnic University of the Philippines.

Christian Bernard Melendez is the Senior Museum Curator of the Museo ng Katipunan, a history museum of the NHCP in San Juan City commemorating the early beginnings of the Philippine Revolution of 1896 led by Andres Bonifacio. He was a BA History graduate from the University of the East.

Ian Christopher Alfonso is currently a Senior History Researcher of the NHCP and a member of the National Quincentennial Committee Secretariat. He concurrently heads the NHCP Local Historical Committees Network. He graduated MA History at the University of the Philippines Diliman and BSEd Social Studies at the Bulacan State University.

Juan Paolo Calamlam is the officer-in-charge of the NHCP Heraldry, a government office responsible in safeguarding the State symbols such as the national flag, national anthem, and the coat-of-arms, as well as regulating the standard of government seals, decorations, heraldic devices, insignias, dry seals, and the likes under Republic Act No. 8491. He graduated BA History at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

Maria Gloria Gabrielle G. Reyno is the current Officer-in-Charge of the NHCP Research, Publication, and Heraldry Division and a Supervising History Researcher. She’s the chief editor of the National Quincentennial Committee website and social media contents. She is also an alumna of UP Diliman.