When Our Ancestors “Discovered” Magellan

Posted on 18 March 2020

By Xiao Chua

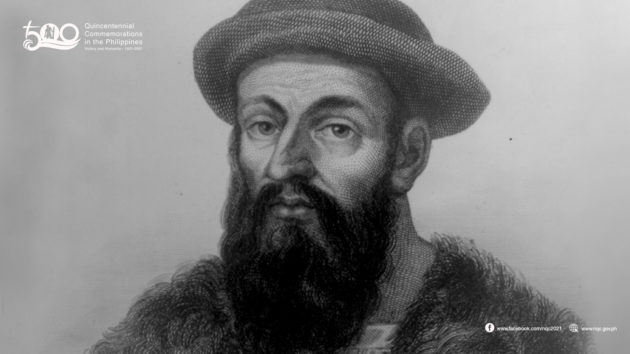

In 2021, the Philippines will join humanity in commemorating the 500th anniversary of the journey of the Armada de Maluco (also known as the Magellan-Elcano expedition) that first circumnavigated the world in 1519-1522. Ferdinand Magellan, the expedition’s captain, and a resolute man, confirmed that there was indeed a route to Southeast Asia beyond America, which was vital for Spain to reach its territories in the region like the Maluku, claimed through the Treaty of Tordesillas. Despite skepticisms of his officials in the Casa de Contratación (Customs House) in Seville, the young Spanish King Carlos gambled on Magellan and later brought him not only profit but unprecedented glory in History: his kingdom had circumnavigated the world (unknowingly) and claimed for Science and humanity the achievement of confirming that the earth was indeed round.

But throughout the journey, the expedition had gone through colorful and action-packed experiences in what is now the Philippine territory in March-April 1521. Technically there was no Philippines during this time but an ancient socio-political order that was based on interdependence and alliances of the islands known as thalassocracy (‘sea power’).

A Sign from St. Lazarus

Since their departure from Guam on 9 March 1521, Samar was the first significant landmass sighted by the expedition on the dawn of 16 March 1521. Spanish chronicler Fr. Francisco Ignacio Alcina, SJ, in his Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas written in 1668, noted that Samar was an international trading area with recorded trade relation with Laos, Cambodia, and China. Expedition’s pilot Francisco Albo was silent about this sighting but documented that on 16 March 1521, the expedition proceeded to a place called Yunagan and Suluan, the latter an island under the jurisdiction of Guiuan, Eastern Samar. Because it was the feast day of San Lazaro, Magellan named the islands they sighted as Archipelago de San Lazaro. The sighting of Samar was later popularized as the “discovery of the Philippines,” which, for decades, has been a subject of debate.

On the same day of sighting Samar, the expedition first anchored in a rocky place called Yunagan located near Suluan, according to Albo. Historian Danilo Gerona identified the place name as the present-day name of Guiuan. Gerona further concluded that the isthmus fitted logically the description of Albo that it had many shoals and down south of it was a “small island” (“isla pequeña,” according to Albo) named Suluan. Because Yunagan was not suitable for anchorage, the expedition immediately transferred near Suluan. There, the expedition sighted our ancestors in canoes but left.

Hope in Homonhon

The following day, 17 March 1521, the expedition made its first landfall at Homonhon, also an island now under the jurisdiction of Guiuan. The island was described by Pigafetta as an uninhabited island. Albo called the place Isla de la Gada, while Gines de Mafra, another crew of the expedition, Aguada (from the moniker to the island Acquada da li buoni Segnialli or the Watering-place of good Signs), for it possessed two springs of ‘clearest water.’ Here, Magellan ordered to set up two tents for the sick and ate a sow (female pig) hunted on the island.

Scholar Luis Francia described this moment as “a revival of their lives if not their fortunes,” mainly because Magellan’s depleting crew—sick and starving for almost four months of braving the Pacific—nourished their selves with the fruits and spring water of Homonhon for nine days. Before reaching the Philippines, Magellan’s sickly crew were requesting their comrades to bring them the entrails of the people they could kill in Guam, in the belief it could nourish them. The expedition indeed almost pushed them to the bounds of reason.

Magnanimity

The following day, 18 March 1521, a group of natives approached the expedition in Homonhon. Upon seeing our ancestors, Magellan instructed his men to do and say nothing unless ordered so. Even though they could not understand the foreigners, the humanity in our ancestors prevailed: an unnamed chief himself (most probably a rajah from mainland Samar, based on the descriptions), who was in Suluan at that time, confirmed the expedition were undernourished and starving. The rajah immediately ordered his men to provide the expedition decent food (i.e., fish, banana, coconut). The Spaniards tasted our ancestors’ palm wine and what was already our staple food—kanin or rice. They also discovered how versatile coconut was in our ancestors’ lives: from drinks, dessert, oil, milk, ointment, and condiments. Reciprocating the kindness of our ancestors, Magellan toured them inside his flagship, Trinidad, and showed them its contents and armament.

This magnanimity showed by our ancestors inspired Magellan to be hopeful of the locals around. The event was the first encounter between our ancestors and the expedition. Pigafetta remarked: “Those people became very familiar with us. They told us many things… We took great pleasure with them, for they were very pleasant and conversable.” Our ancestors visited the expedition again on 22 March 1521.

Pigafetta described the unnamed rajah as a tattooed old man sporting gold ornaments and earrings, a bandana, and a cotton dress embroidered with silk at the ends. This description is corroborated by the illustrations of the Visayan noblemen found in the ca. 1590 Boxer Codex of the Indiana University.

Bookending an Episode

History gives us pride and dignity as Filipino: when the Spaniards first came to the Philippines in 1521 through the Magellan-Elcano expedition, our ancestors in Homonhon showed them compassion; and if not for this, that expedition could have given up offering humanity an unprecedented achievement—to circumnavigate the world for the first time. Once again, more than 300 years later, our forebears in 1899 showed the world an example of how to treat an enemy: they fed and patiently waited for almost a year, from 1898 to 1899, the surrender of the last Spanish soldiers in the Philippines who sought refuge inside Baler Church, now in Aurora. It paved the way to the signing of Philippine President Emilio Aguinaldo in Tarlac of a decree on 30 June 1899 providing a safe-conduct pass to these last Spanish soldiers and recognizing them as friends of the Filipino people. It later became the basis of the annual Philippine-Spanish Friendship Day.

Legacy of Compassion

The theme Victory and Humanity of the 2021 Quincentennial Commemorations in the Philippines (2021 QCP) is inspired by the victorious spirit exemplified in the Battle of Mactan in 1521; while humanity stems from the helping hands of our ancestors exemplified at Homonhon. The National Quincentennial Committee (NQC) will underscore that magnanimity in Homonhon, an often-neglected episode in the history of the first circumnavigation of the world.

To further debunk the politically incorrect idea that Magellan discovered the Philippines, the NQC reoriented the thrust of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the Magellan-Elcano expedition as a co-celebration of the Filipinos with humankind in the latter’s achievement of circumnavigating the world for the first time. As a statement to this, the NQC rebranded the arrival of the Magellan-Elcano expedition as the anniversary of the Philippine part in the first circumnavigation of the world. It is supposed to be implemented on 16-17 March 2020 in Guiuan. The placement of Metro Manila under community quarantine owing to the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19) effective 15 March 2020 prevented the NQC from joining the Eastern Samar Provincial Government and the Guiuan Municipal Government.

The NQC also envisions that the 500th anniversary of the Philippine part in the first circumnavigation of the world will boost the morale of the Filipinos: that we are innately compassionate and magnanimous people, to the extent we cheer for other countries like Timor-Leste during the 30th Southeast Asian Games. We’ve been through hardships in history; we were alone when we were starting as a nation in 1896 and asserted our right to be free in 1899, with no single country expressing outright intention to extend help. But we reciprocated these with humanity, like how we opened our doors for the Jewish refugees during World War II while no other country willing to shelter them in 1939 (and we were just a rising country aspiring to be a republic back then); as well as to the White Russians (anti-communists) who were expelled out from China by the communists in 1949, and no one dared to shelter them (and we ourselves were still rising from the ashes of World War II); and many more episodes in history we should be proud of.

No wonder why we Filipinos are people of the world. We build the world. We care for our fellow humankind. –With additional notes by Ian Christopher Alfonso

For further reading:

Escalante, Rene R. 2019. National Quincentennial Committee Comprehensive Plan. Manila: National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

Francia, Luis. 2010. A History of the Philippines. New York: Overlook Press.

Gerona, Danilo Madrid. 2016. Ferdinand Magellan: The Armada de Maluco and the European discovery of the Philippines. Naga City: Spanish Galleon Publishing.

Pigafetta, Antonio. 1906. Magellan’s Voyage Around the World (3 volumes), James Alexander Robertson, trans. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark.

Scott, William Henry. 1992. Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino and Other Essays in Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

_____. 1984. Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

About the Author

MICHAEL CHARLESTON “XIAO” CHUA is a public historian and Assistant Professorial Lecturer of History at the De La Salle University Manila. He is the author of a number of refereed academic journals and a columnist at the Manila Times and Abante. He was the creator of Xiao Time, the history segment of the government television station.