History and Culture Intertwined with Nature

Posted on 27 March 2021

By National Quincentennial Committee Secretariat

This Earth Hour, let us discover how our ancestors view the world based on written records and on the folklore and belief system of our indigenous peoples and of our respective ethnic groups.

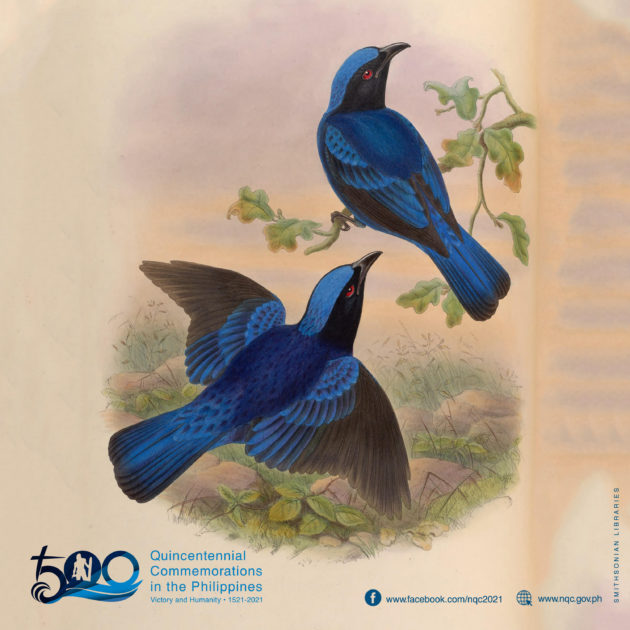

Like how our ancestors revered a bird called bathala (Irena cyanogastra or the Blue-mantled Fairy Bluebird) as a representation of God on earth. According to Spanish chronicler Fr. Francisco Colin, SJ, the bird was also called tigmamanok among ancient Tagalogs, mamanok by the Kapampangans, and mammanok to Ilokanos. And because God in Christianity, in His persona as Holy Spirit, is also represented by a bird, our ancestors immediately saw the connection.

Moreover, in our veins run the blood of the ancient maritime people. Our very names are evidence of this: we call ourselves Ilokano (people of look or ‘bay’), Tausug (people of the sug or ‘current’), Subanon (people of suba or ‘river’), Palawan (people of the palaw or ‘island’), Tagalog (people of the alog or ‘shallow waters’/ilog or ‘river’), Maranaw (people of danaw or ‘lake’), and Kapampangan (bordering the pampang or ‘riverbank’). Our folklores have gods and goddesses riding in flying boats; we imagine that the aldaw (‘sun’) is lumulubog (literally ‘drowning’ but it means sunset) and sumisikat (literally ‘rising’), and is being devoured by the bakunawa (‘sea dragon’ among the Visayans) during lawo (‘eclipse’). Our ancient writings follow the contour of the rivers or shores. Our ancient communities, named after balangay or ancient boat, were once connected by rivers–those residing by the iraya (‘headwaters’) and those by the ilawud (‘downstream’). Ancient Kapampangans called their fellow barangay-mates kabangka (‘kabarangay’).

The kabilang buhay for our ancestors was an extension of our maritime world. Kabaong or coffins in ancient times were shaped like bangka or sea vessels (thus, the cadaver is bangkay). The cap of the Manunggul Jar of Palawan depicts a bangkero or oarsman transporting the bangkay in a boat to kabilang buhay. While the ancient gravesite markers of the Ivatans in Batanes and of the Sama-Bajaus in the Great Santa Cruz Island in Zamboanga City are shaped like tataya (boat in Ivatan) and lepa (boat in Sama-Bajau). The hanging coffins of Sagada, Mt. Province are also boat-like. Our ancestors also practiced reinternment by collecting the bodily remains (kalansay) of their departed loved ones and containing them in a banga or jar, like the Manunggul Jar and those discovered in Maitum in Sarangani Province. Through this practice, our ancestors seemed to bring back the physical body of their loved ones to the representation of a mother’s womb (which was the banga)—most likely the same idea when a bangkay was placed in a boat-shaped coffin, for the boat was universally likened to a mother.

Our culture and history are intertwined with mother nature. As we reconnect ourselves with the past, we must also find ways how to see ourselves as caretakers of our home planet.