Cebu and Southeast Asia During Magellan’s Arrival

Posted on 07 February 2021

By Van Ybiernas

Among the interesting things to know about the pre-Hispanic Philippines is our ancestors’ contacts with the neighboring peoples of various kingdoms and empires. In doing so, it is necessary to understand the dynamics, and conduct of our ancestors’ dealings with their neighbors back then, through the lens of maritime trade.

Port Cities-Empire Connection

Before Ferdinand Magellan came, there were riverine and coastal communities in the pre-Hispanic Philippines that used to be entrepôts or places where goods were imported and redistributed. These entrepôts were strategically located on bodies of water suitable for anchorage or at the mouths of rivers, then the ancient superhighways for accessing communities in the interior or upland (e.g., ilaya, iraya, saraya) or within a group of islands. Historian William Henry Scott noted that these ancient economic centers were ruled by a ruler called rajah (also spelled as ladia, raha, lasang, raya, and laya in various Spanish accounts), obviously, an Indian influence predating the coming of Islam and Christianity in the Philippines. Timawa or freemen (also called kabangka [literally ‘fellow boatmen’] or constituents in Kapampangan) gave reverence to him and paid regular dues called buhis or handug in the Visayas. He had the sole authority to collect anchorage fees and negotiate with foreign merchants. He was also the lone distributor of the goods within his jurisdiction. This was true in Luzon, an island north of the Philippines originally pertaining to the communities surrounding Manila Bay including Mindoro and Lubang. The area was ruled by two rulers: a lakan (also an Indianized title) and a ladia (variation of rajah). The demarcation of the two was the Pasig River; the lakan ruled on the north bank, while the ladia ruled the other side. The north Pasig was called Tondo, while the south was Manila. Rajah was also the title of the rulers in Cebu, Mazaua, and Butuan according to the Magellan-Elcano expedition’s chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta.

Like any other Southeast Asian entrepôts, those in the pre-Hispanic Philippines were frequented by foreign traders such as the Chinese, Japanese, and ancient Indonesian Indianized empires. Vestiges of their influences on our ancestors can be observed in our inherited languages, customs, folklore, traditions, religion, world view, writing system, and oral literature.

Our ancestors had active relations with other entrepôts within Southeast Asia. Evidence to this is Pigafetta’s record of Cebu having contact with Siam (Thailand), as well as the artifacts continuously being discovered in various parts of the Philippines. Pre-Hispanic Portuguese account, likewise, mention the Luções, or the people from Luzon, who were either trading and residing in Melaka or serving as mercenaries for the Ottoman Empire’s campaign against the Portuguese and non-Muslim natives in Sumatra. Also worthy to be noted as proof of our ancestors’ interactions with their Southeast Asian neighbors is their use of the colossal Southeast Asian warships called kora-kora (caracoa by the Spaniards) from the Maluku.

Our Ancestors’ Ancient Connection to Each Other

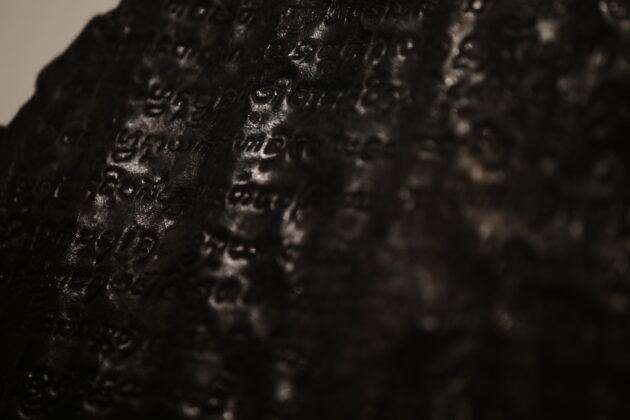

Dynamics between the rajahs were recorded by Pigafetta. One of this the close relationship between the entrepôts of Mazaua and Cebu, which, according to Pigafetta, were the two most powerful territories in the Visayas. If proven authentic, the 1589 last will and testament of a certain Fernando Malang Balagtas of Tabungao, Minalin, Pampanga claims that the translator was the old lakan of Tondo and was baptized in Cebu in 1521. Nonetheless, this was not surprising because the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, the earliest known Philippine document found locally dated AD 900, establishes the connection of Tondo and Mindanao (i.e., the pamegat senapati or Commander in Chief of Tondo intervened in clearing the debts of a family in Luzon from the pamegat or chief of Dewata, now part of Butuan in Mindanao).

Rajah Humabon’s Ambition

It is also equally important to understand the military benefit an entrepôt could gain from the foreigners. During their negotiation, Rajah Humabon of Cebu decided to welcome Magellan despite the latter having no means of paying anchorage in Cebu. This was because Magellan promised the rajah of Spain’s protection against his enemies. Humabon was swayed by Magellan’s boasting that the Spaniards were more powerful than the conquerors of the entrepôts of Melaka and Kolkata—the Portuguese.

The alliance between Humabon and Magellan exemplifies the observations of the Spaniards on our ancestors’ political system: while a rajah was paramount in the social hierarchy, he had no authority over datus or chiefs of the barangay or villages—precisely the reason why Lapulapu, a chief of Mactan, did not recognize the rajah (resulting to the Battle of Mactan on 27 April 1521). According to Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, our ancestors revered no kings such as those in Europe except their datu. Every barangay was autonomous.

In the end, the Humabon-Magellan alliance failed to benefit either of them and even led to Magellan’s death in Mactan.

Postscript

Southeast Asia found by Magallanes had a bustling trade going on among the region’s major entrepôts. Such was the case of great Asian empires, e.g., Brunei and China, vice-versa; the secondary entrepôts, e.g., Cebu and Siam, vice-versa; and the secondary entrepôts with their outlying islands/interior/upland communities, e.g., Cebu and Mazaua, vice-versa. This flourishing trading was interrupted only by the Portuguese and Spanish colonization of Southeast Asia. In the case of the Philippines, the Spaniards restricted our ancestors from trading with other islands and entrepôts out of fear of destabilization. This almost happened in 1587-1588 when leaders of Luzon, Borneo, and Japan conspired to overthrow the Spanish regime in Manila.

Recommended Readings

Hall, Kenneth R. 1985. Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Junker, Laura Lee. 1999. Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Milner, A.C. 1982. Kerajaan: Malay Political Culture on the Eve of Colonial Rule. Tucson: Association for Asian Studies.

Pigafetta, Antonio. 1906. Magellan’s Voyage Around the World (3 volumes), James Alexander Robertson, trans. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark.

Ptak, Roderich. 1992. “The Northern Trade Route to the Spice Islands: South China Sea-Sulu Zone-North Moluccas (14th to Early 16th Century).” Archipel 43, 27-56.

Reid, Anthony. 1988/1993. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680; I, The Lands Below the Winds; II, Expansion and Crisis. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tarling, Nicholas, ed. 1992. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, 2 volumes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tiongson, Jaime Figueroa. 2013. Ang Saysay ng Inskripsyon sa Binatbat na Tanso ng Laguna. Quezon City: BAKAS.

Van Ybiernas is an economic and public historian.